Empowering Neural Engineering

A group of innovative, accomplished faculty is driving the field forward, working side-by-side with clinicians in the U-M Medical School to focus on translational applications to improve the lives of patients.

A group of innovative, accomplished faculty is driving the field forward, working side-by-side with clinicians in the U-M Medical School to focus on translational applications to improve the lives of patients.

Some of the earliest neural engineering work in the field was – pun unintended – conducted at U-M, including the invention of the first silicon neural electrode by Kensall Wise, professor emeritus of BME and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Today a cluster of innovative, accomplished faculty is driving the field forward, working side-by-side with clinicians in the U-M Medical School to focus on translational applications to improve the lives of patients.

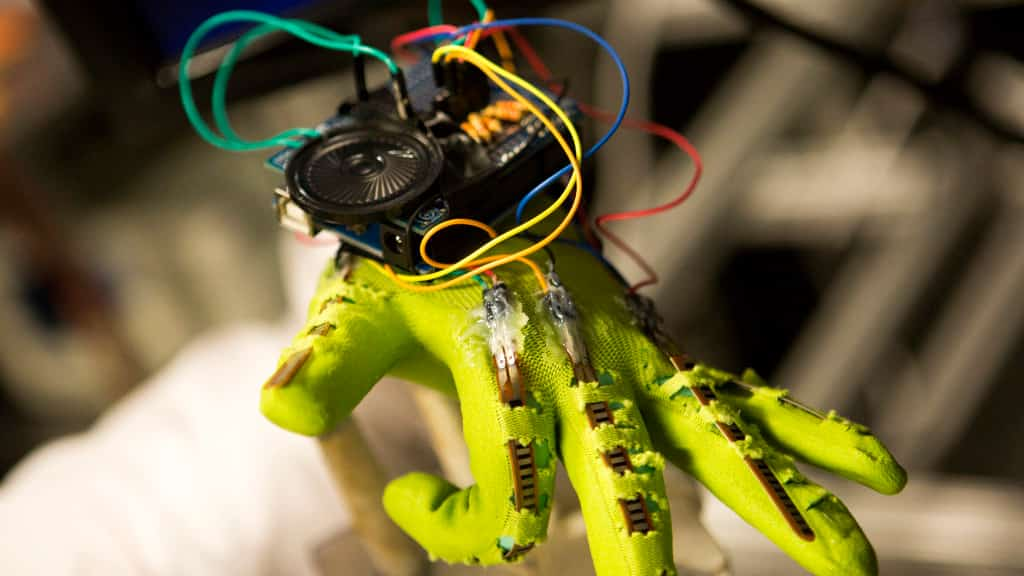

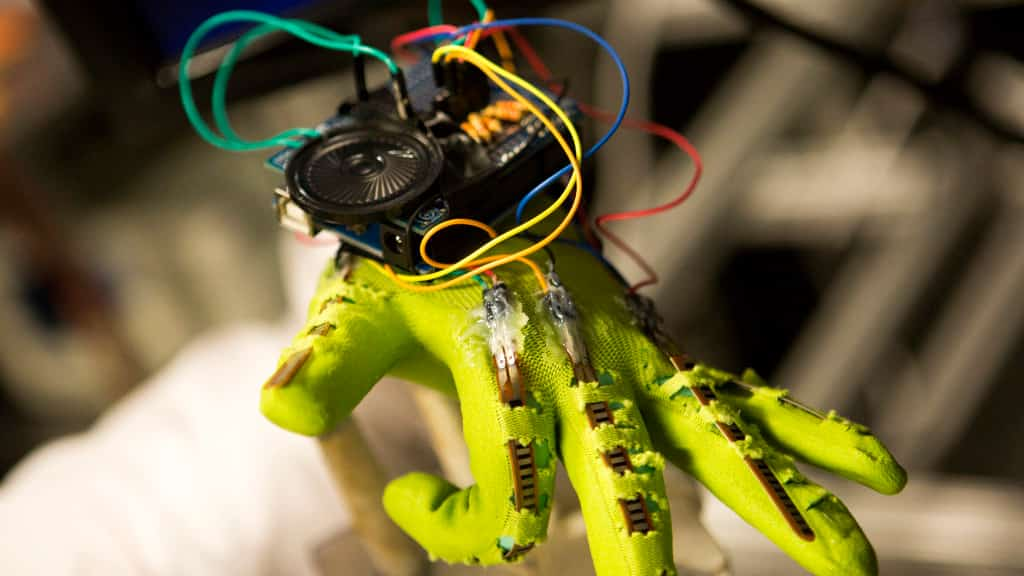

Chestek’s lab works to restore natural movement to individuals who have lost the use of their hands, whether due to amputation, spinal cord injury or other cause of paralysis. Her work includes improving neural signal control of prosthetics and natural limbs through novel and improved brain-machine interfaces, functional electrical stimulation and assistive exoskeletons.

Toward that goal, Chestek and collaborators are developing new electrodes. She and Professor Euisik Yoon recently demonstrated an eight-micrometer carbon-fiber probe. Research to date has shown that the probes cause significantly less scarring and immune response than conventional larger electrodes.

In a collaborative project with Parag Patil, MD, to develop a system for brain controlled functional electrical stimulation, Chestek and her students apply machine learning algorithms to neural signals recorded by 100-channel implanted arrays. Using Kalman filters and regression techniques, the objective is to understand the relationships between hand movements and their respective neuron firing rates.

In collaboration with Paul Cederna, MD, professor of surgery and chief of plastic surgery, Chestek’s lab has been conducting pre-clinical work on hand control using neural signals. One of the barriers to nerve-controlled prosthetic limbs has been the small signal. The team’s work found muscle grafted to the ends of split nerves – a procedure Dr. Cederna performs on patients suffering from painful nerve growths following amputation – can amplify neural signals to the point they can control a prosthetic hand.

Chestek joined the BME faculty in 2012 and jokes that she will be here forever. “At U-M, we have a Top 10 engineering school and a Top 10 medical school — I came here for the very strong collaborations and, because of the doctors, I’ll never leave. I collaborate with a surgeon on every project. There’s a fertile group of clinicians here who are deeply invested in this technology and to bringing it to clinical practice.”

For the 25 million Americans and countless others around the globe who suffer from chronic pain, Lempka’s work holds great promise. Research in his lab focuses on neuromodulation for managing chronic pain and, although such techniques have been used for years, only about 50 percent of patients get relief. In those who do, however, it’s often not enough to make a real impact on their quality of life.

To identify and better understand the specific mechanisms by which neurostimulation works, and why it works for some patients and not others, Lempka’s group takes an engineering approach to develop patient-specific computer models. The models are generated from quantitative and qualitative clinical data, obtained from CT, MRI and functional MRI imaging, and how patients respond to different stimulation parameters.

In recently published work, Lempka and colleagues describe a first-in-man clinical trial of deep brain stimulation for post-stroke pain that targets alternate pathways, specifically those related to emotions and behavior, rather than sensation. The areas targeted, the ventral striatum/anterior limb of the internal capsule, have been widely studied and safely used in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder and refractory depression. Although pain intensity wasn’t significantly reduced in the study, participants’ reports of anxiety and depression related to the pain were.

“This tells us we should consider changing what we consider a success with these neurostimulation therapies. Rather than fixating on pain intensity, we should shift our focus to reducing pain-related suffering or disability,” says Lempka, who joined the BME faculty in January 2017 and is excited about further research. “Working with U-M’s clinical pain research groups and pain management specialists will help us not only better understand how neurostimulation works on pain but also to develop innovative and more effective patient-specific therapies.”

Lempka, S. et al. Randomized clinical trial of deep brain stimulation for poststroke pain. Annals of Neurology, 2017; 81 (5): 653; DOI: 10.1002/ana.24927.

Weiland is co-developer of a bioelectronic retinal prosthesis, or so-called bionic eye, which electrically stimulates the retina and can partially restore vision to individuals who have lost their sight due to inherited retinal disease. The Argus II was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2013 and has since been implanted in over 200 people worldwide, including 10 at the Kellogg Eye Center at U-M.

Weiland’s BioElectronic Vision Lab investigates the fundamental mechanisms underlying the ways in which implantable and wearable electronic systems interact with the natural visual system and other senses. He has demonstrated the feasibility of using MRI and fMRI in patients with the retinal prosthesis to better understand how the visual pathways in the brain respond to sight recovery and also how these pathways adapt to process other sensory input, including tactile input, in a phenomenon known as cross-modal activation.

In addition, Weiland and researchers in his lab are studying how these prosthetic systems affect the anatomy and functioning of the visual system over time in order to optimize existing and future devices. His lab is also developing a wearable, smart camera system that can work with the Argus or as a standalone assistive technology for the visually impaired.

Findings from these studies will lead to further refinements to the Argus II to enhance vision restoration. Involving Argus patients in evaluating design changes is a key aspect to his research program.

Weiland earned his MS and PhD degrees in BME and returned to campus to join the BME faculty in January 2017, after holding faculty appointments at Johns Hopkins University and University of Southern California.

“Ann Arbor has always been a second home for me,” Weiland says. “When an opportunity became available to join the BME department, it was difficult to not explore the possibility. The more I visited and talked with faculty and students in BME and Ophthalmology, the more the move made sense. The excellence of the engineering and medical schools was a strong attraction.